I’ll admit it: despite being in my forties, I was totally charmed by the Netflix coming of age comedy “Never Have I Ever”. The character Paxton Hall-Yoshida (played by Darren Barnet) is the resident popular kid and captain of the swim team, as well as the crush of protagonist Devi. Watching the show got me thinking about how Paxton’s postural patterns contribute to who his character is. That being said…….

Paxton, dude, it’s time to get Rolfed!

Don’t get me wrong, Barnet is obviously a very good looking kid, but having to beef up for his role as Paxton, he is facilitating postural patterns that will not serve his structural well-being in the long run.

Let’s dissect what goes into looking like a cool guy:

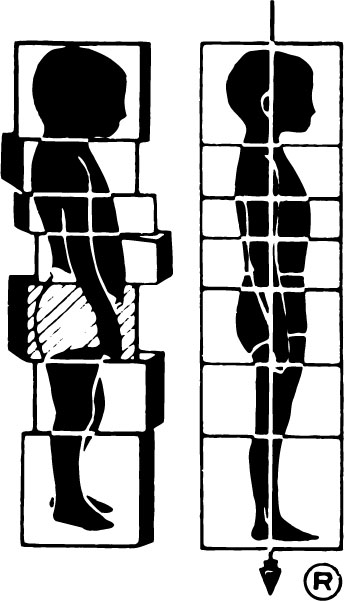

If you’ve watched the show, notice that as Paxton walks down the hall, he’s perpetually sidebent left (just like in the photo above). He really only likes to rotate to one side (it changes if he has a backpack on), and he walks with his shoulders moving up and down, instead of forward and backward. He really prefers to mostly move in the coronal plane (a vertical plane running front to back). Because his spine rotates in a very limited capacity, this in turn reduces the ability of his arms to swing forward and back. You may notice a similar pattern in his hips and pelvis. They also primarily move in the coronal plane, so it looks a bit like he’s teetering side to side when walking. This makes his stride very short (or at least, what I can see of it as he walks down the school hallway), which limits the amount of extension he’s getting in his hips. When we walk, we need movement in all three planes (more info on this in a future post!); without it, we begin to experience movement restriction and increased pressure in the abdominal and reproductive organs.

Part of Paxton’s pattern has to do with the fact that his trunk and front are perpetually flexed, which contributes to his sculpted abs, but which restricts the ability of his pelvis and spine to move freely in the three planes of motion.

We humans need dispersal of kinetic energy when we walk. We experience this when our arms and legs are able to swing freely. When there is restriction (due to excess tension) or inhibition (due to lack of proprioception or trauma), we feel rigid. This is when we veer onto the path towards decreased function, and possibly pain. Paxton doesn’t get this dispersal of kinetic energy, which means that energy is being stored somewhere in his structure as a holding pattern. Of course, he’s young enough, so it’s probably not even on his radar yet.

With his shoulders internally rotated and pulled forward, his pecs are highlighted, but can you also see how there’s a drag from the sternum down to his upper abdominals? The respiratory diaphragm is a dome shaped musculotendinous structure that attaches to the sternum, the last six ribs, as well as the lumbar spine. Imagine what happens when the diaphragm is squished: not only is breathing capacity reduced, but because the phrenic nerve runs through the diaphragm, it can also compromise one’s ability to regulate oneself.

The way Paxton moves is his personal kinetic melody. Your kinetic melody is unique to you, and can be thought of as your personal movement signature. Each one of us has our own melody, formed from our life experiences, perception, orientation, patterns and habits. These we enact through a certain rhythm and sequence. The neurologist, Oliver Sacks, explains it: “When we walk, our steps emerge in a rhythmical stream, a flow that is automatic and self-organizing.” When the movement is halting and broken, perhaps caused by a disease such as Parkinson’s, it is called a kinetic stutter.

The kinetic melody is how you can identify a friend walking down the street, even from a far distance, when you can’t see their facial features clearly. Perhaps you even feel your friend’s rhythm echoed in your own body, as something familiar.

How we learned to move as infants, toddlers and children is primarily nonverbal. We take in the kinetic melodies of our caregivers, and try them out in our own bodies. We unconsciously model these adults, adopting their movement strategies, for better or for worse.

Paxton’s posture reflects who he is. The way he walks communicates a laid-back California vibe. This is what Rolf Movement teacher Aline Newton calls “posture as attitude”. His asymmetric gait communicates something of his personality and life philosophy. If Paxton was ramrod straight with his head perfectly aligned over his shoulders and pelvis, would he be believable as a Gen Z?

Oh Paxton, if you came to my Rolfing practice, I would spend some time balancing your front and back, opening your thoracic inlet, and mobilizing your thorax. I would tell you to stop working out your trapezius muscle and your pecs, and to stop contracting/flexing your front, so that in your old age, your pelvic floor would be more functional. I would work with you to mobilize your hips so that your pelvis and SI joints could move freely in all three planes. Once I get sorted out on social media, I’ll DM you……..